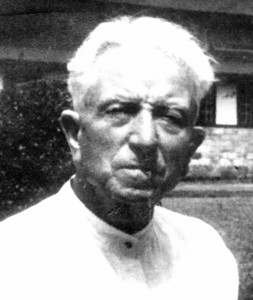

BROTHER JOHN EVANGELIST McCANN

(1890 – 1972)

D. E. Hayes

We know what manner of man John Evangelist McCann was: his confreres and relatives, his acquaintances and friends, his pupils and their parents would all attest without reservation that he was the very personification of “the complete man.” The old and the new, tradition and progress, conservation and experiment were happily blended in his ample, rich vision of life. An evaluation of the circumstances, forces, graces, experiences, environments that combined to enrich the Congregation in the person of this exceedingly worthy son of Edmund Rice might inspire his fellows to make their lives even more sublime.

He was born in Belfast on 26 January 1890, the eldest of a family of eight, five boys and three girls, and christened John James and he became know to his family as Jim. His father, Patrick, hailed from Cavan; his mother, Wilhelmina Miller, from Belfast. Mr. McCann was a sergeant of the Royal Irish Constabulary; so the family, because of transfers, knew many homes and many neighbours. John attended schools in Belfast, Louth, Drogheda, Tallanstown, and finally Dundalk CBS, where he did an Intermediate Examination in 1905. They were a happy, well-knit, outgoing family, who adjusted easily to their changing environment; they took adaptability in their stride, they mixed well and were sociable and neighbourly. The occasional quarrel – inevitable in a healthy group of youngsters bubbling with spontaneity and wonder was sometimes overlooked by wise parents and sometimes made an issue of; and punishment was even-handedly meted out. Reconciliation followed and the irrepressible youngsters resumed the joyous business of living and laughing, little the worse for wear. Authority in the household was hierarchical, with John by virtue of seniority and not a small degree of natural leadership occupying the third place.

Then into those halcyon days stalked tragedy. In 1902 Mrs. McCann, that valiant woman, grew ill and died, leaving a heart-broken husband and a bewildered, uncomprehending family numbed at their loss. This shattering traumatic experience was shared by all the children to the degree that their understanding could grasp it – most of all by John, the eldest, then a lanky twelve-year-old. His kindly nature managed to sublimate his sense of loss and grief into a fine sustained effort to become a substitute parent to the younger children. He was a tower of strength to his father in filling the new role circumstances called on him to play, and young John, now number two in the family, undertook loads of household work which had to be got in before and after school each day. In seeing to the needs of his younger brothers ad sisters he developed a fine insight into the very heart of children, and an inexhaustible measure of patience. His father relied heavily on him despite the boy’s occasional lapses and so managed to fulfill his duties in the police force and maintain the family. Thus did Providence pave the way for the untold service to thousands of children that young John was destined to render and for the mighty responsibility he was ultimately to bear.

The McCanns gradually adjusted to their grievous loss, and in time the genial family environment was restored, thanks in part to the emotional stability John set out to acquire in order to engender confidence and a sense of security in the others. The challenge was great and he met it squarely with remarkable success.

His father was a man of robust faith and courage, tested mightily when his wife died and tested again three years later when in 1905 his eldest son, fresh from his Intermediate Examination and a potential extra bread-winner, decided to become a Christian Brother. Mr. McCann proved to be another Abraham and consented. No so his brothers and sisters. “When he went away in 1905,” recalls his brother Leo, “he left behind him seven very lonely and sad little boys and girls, who wished he had stayed at home.” He adds, “Jim was my favourite brother and I’m certain he was the favourite of all my brothers and sisters. We can all remember him as a kindly affectionate brother working very hard at the job of trying to replace Mother, who died when most of us were toddlers.” The youngest was only two.

At that time John was a fine athletic youth, tall and virile, and full of devilry. His dynamic, enterprising nature landed him in many a scrape but his resourceful mind found a way out with equal facility. He did not impress his father as the best possible raw material for the making of a Christian Brother as can be gathered from John’s own words to his brother a few days before his death. “When my father delivered me at Baldoyle on 29 June 1905 he told me he would be back shortly for me because, he said, he knew I would never stick it.” Time and God’s grace proved that Mr. McCann could not be wider of the mark.

John took the juniorate in his stride. Its blend of study and prayer, games and outings, community living and periods of quiet meditative reflection suited his sanguine temperament and modified his robust pranks, not to mention his penchant for practical jokes. Being naturally brilliant and endowed with an excellent memory he eagerly engaged in the course of studies pursued, which stimulated his many interests and tastes. Even then he read avidly and widely, and those fellow-postulants of his who found Latin or mathematics too difficult to master received his unstinted help. The friendly service he had rendered to his brothers and sisters at home was simply transferred to his new family, and remained an abiding trait of his personality during his long life. His sense of responsibility, heightened above the average by three years of fending for a motherless family, caused leadership and initiative to gravitate towards him and stamped him with a special charism.

On Christmas Day 1905 he received the habit and took the name of John the Evangelist as his patron – a most significant choice. Evangelist, the proclaimer of the Good News, flawlessly fitted his character and personality and never did he cease to tell the world that it was a joyous thing to be alive, to take the Gospel at face value, to participate as a religious teacher in God’s creative design, to trust in God’s loving care and thus be free for positive action. He effected the proclaiming just by being himself, a buoyant, extroverted religious brimming with joie de vivre. This was no vapid, mindless exuberance – he had plumbed the depth of sorrow more than most youngsters – it was the visible overflow of a man who understood his own nature and the power of God’s grace and not a little of the world and the times he lived in.

His year of formation was for him a year of toil. The sowing of the seed was difficult, irksome work but with earnestness and perseverance the grain of wheat began to germinate – aided by a careful gardener, the novice master, whose pruning and digging and watering (which took the shape of penances, conferences, advice and encouragement) eventually produced a bumper crop. For his part Evangelist was selective of the variety and richness of the fare offered to nourish his spiritual life. Not for him the easy strait jacket of unimaginative adherence to a blanket formula that could smother his full flowering as an individual and warp his personality. He continued to be himself, the strong youth (sometimes headstrong) hailing from a happy and outgoing family that had tasted deep tragedy and still remained genial. But that open self, now more exposed to the promptings of the Spirit, palpably grew and waxed strong. Evidence of the emergence of the complete man from the chrysalis of the stalwart youth were there for all to see.

By the year’s end Evangelist stood almost six feet tall, quite distinguished by his untamed shock of black hair (never tamed and never lost – the years bleached it silver-white) and in a state of readiness for the adventure and the challenge of the Christian Brother’s life. The short intense course of academic-cum-professional training that ensued equipped him for his first mission, Carlow, in August 1907. Here a nasty bout of flu laid him low and the persistent cough that followed drained his vitality and gave cause for anxiety. So in November he was transferred to Synge Street, where he would receive better medical attention. Brother Joseph O’Brien (one of our uncanonized saints) became his beau ideal in this community and it was through Joseph that the Spirit worked in Evangelist to deepen his commitment.

He was now three months short of eighteen years and doing a great job of teaching in the junior school, which he accomplished with a zest and verve that was to be one of his distinctive characteristics. His manly bearing and clipped accent (a flavour of the North), his earnestness and buoyancy, his carefully prepared lessons, his ability to identify with youngsters, and his sense of fair play all made an unbeatable combination in this tyro teacher – and the pupils thrilled to him. He became their hero. He used his prestige position for their maximum benefit. What eight-year-old could bear to be absent from his confession-preparation class when the Brother made the Bible stories come so vibrantly alive? When Brother was saddened by misdemeanor because God, our Father, was displeased there was only one course of action left, and that was to repent, confess, and resolve, and pray to Christ, our elder brother, for greater strength.

Then suddenly came the call to India after one short year of the Irish mission. After a brief visit home to Belfast to bid goodbye to his family and suffering the pangs of ‘the little death” (Partir est mourir un peu) he sailed for India with Cyprian Corbett and Baptist Collins and arrived in Calcutta on 18 October 1908. Cyprian died of smallpox four months later. Baptist served with the IndianProvince with distinction for over forty years and then joined the EnglishProvince.

Evangelist’s new mission on the Sub-Continent occasioned yet another form of dying: the adjusting to the Calcutta climate. His experience over the next two years as a member of the St. Joseph’s (Calcutta) community could be paralleled with his novitiate formation. It involved anew the widening and deepening of his commitment under extremely trying physical circumstances so that he could continue to be an effective instrument of God’s grace. Characteristically he met the challenge head-on.

The temperature in Calcutta from March to June is normally over 100F; the humidity touches 100%. A heatwave during this period (and there are several) pushes the mercury close to the 120F mark. The monsoon brings a measure of relief with an average temperature of 95F. The winter (December-January) is comparatively tolerable, the mercury being merely in the high 70s.

To such a climate Brother Evangelist, now in his nineteenth year and to whom hitherto a temperature of over 80F was only academic, adapted himself with a will. He deliberately would not permit the blistering heat of the searing city to lessen or impair his output of work. He found the going rough of course, especially the sleepless nights when the whole house seemed a furnace, when the mosquitoes attacked just at the moment of his drifting off to sleep and when, eventually, towards dawn blissful slumber took over, it seemed to be shattered instantly by the clanging of the bell, announcing a new day and a fresh beginning. It is doubtful if John Evangelist McCann every succumbed to weary nature and closed his ears and his conscience to the bell call. He was up and about at once and, shaved and spruce, joined the community in the praises of the Lord. In those days the brothers wore their black habits at Mass, and afterwards took them off, sodden with perspiration, to don white cotton cassocks more suited to the climate. And so the unending round of daily prayer and work went on despite the discomfort of continual perspiration and resultant prickly heat (the hair-shirt of the tropics!)

Evangelist spent two years in Calcutta, which short period heralded a series of fairly rapid transfers – the normal lot of the young Christian Brother and a valuable element in his growth – and so we find him in Goethals (Kurseong) from 1911 to 1913, back in Calcutta in 1914, in Naini Tal from 1915 to 1918, where in December 1915 he took final vows, and again back in St. Joseph’s (Calcutta) from 1919 to early 1923. He is now a well-seasoned Christian Brother. For him these changes merely reflected the kaleidoscope of his boyhood years and imparted greater flexibility to his adaptable nature. They widened his range of interests and deepened his understanding of the nature of his vocation. They were years of crowded activity. There was the work of the classroom, itself exhausting in the humid sweltering climate of Bengal; there were the co-curricular activities in which Evangelist gave of his best whether as a skilful scout master or as a stimulating director of dramatics; there were the daily stints of study when he prepared for the grade examinations – and how well he and many more of the old brothers benefited from those grades to equip themselves for their life-work!

In March 1923 he was appointed superior of St. Edmunds College, Shillong. Brother Stanislaus O’Brien, brother of Joseph O’Brien of Synge Street, then community chronicler, succinctly states, “This is his first directorship but he should do well. He has had long experience in India although he is a young man, and he is a thorough school man.” Stanislaus proved quite accurate in his summing up of the new distinguished-looking director. Evangelist’s potential was already evident; his total personality bespoke, with Robert Frost, “promises to keep.” He kept them.

He proved to be as fine an administrator as Stanislaus predicted. The annals show that even in those far-off days the principle of subsidiarity guided his service to the community and school, with different brothers and lay teachers responsible for their allotted tasks, he himself being the co-ordinator. He was scarcely a month in office when he was struck down by the dreaded disease, enteric, after previously spending most of his free time at the bedside of a boarder who was convalescing from the same fever. Evangelist spent ten weeks in hospital and in the early stages his delirious condition frequently gave rise to grave anxiety. His strong constitution and the tireless care of stone-deaf Nurse Evans eventually brought him through though his emaciated frame took months to recover Nevertheless he forged ahead with his plans and succeeded in securing affiliation of the college with the University of Calcutta up to the Intermediate Arts and Science standard. In the college he taught Latin to the 1A Class and was class master of Class 9 in the school.

Early in 1924 a series of nightly mysterious thefts of clothing from the boarder’s linen room clamoured for an urgent solution. Evangelist, in prankish mood, set the trap. He secretly concealed a wire in the linen room and set up an electric connection from it to a bell in his own room, a hundred feet away. When at 2 a.m. the tinkling of the bell awakened him he quietly called some senior boys, more than eager to co-operate, who surrounded the room. They caught one of the two nocturnal visitors – the accomplice on the qui vive got away- and handed him over to the police. Later the thief, who bore the unlikely name of Angelus, confessed that he and his companion, who were carpenters by trade, simply unscrewed a window and afterwards replaced it and vanished loaded with loot. In later years Evangelist loved to tell the story of Angelus.

The beautiful chapel in St. Edmund’s stands as a monument to Evangelist’s memory. It was completed in 1927 and represented a new trend in buildings in the Khasi Hills, an earthquake area, where houses are commonly erected with interlacing bamboo and plaster and wood. His chapel was a prototype of the ferro-concrete structure and has proved its resistance to earthquakes for nearly fifty years in an area where the seismograph records an average of twelve tremors a day. Most large new building in the region are today ferro-concrete.

The fact that, at the provincial chapter held in Kurji in February 1925, Brother Evangelist was one of the four elected members – the others, eight in number, being ex officio – shows the high regard the province had for this 35-year-old brother. His term of office as superior in St. Edmund’s having come to an end in December 1928, he and Brother Cyprian Roe sailed to Ireland in April 1929 for a holiday, this being his first visit home in twenty-one years.

Thereafter the kaleidoscope begins flickering again, yielding St. Michael’s (Kurji) and Goethals (Kurseong) each for a period of two years as sub-superior; and then, in January 1934, St. Patrick’s (Asansol) as superior. His arrival in St. Pat’s coincided with a severe earth-tremor, the subject of much banter later between himself and the brothers. It was violent enough to topple part of the building. This was his first serious set-back because the year’s budgeting did not envisage major repair work and the rupees for even small contingencies were few. Here the young brothers in the community who had not yet made his acquaintance were really impressed by his charming personality and friendly nature. They responded in kind and the school flourished. Here was a leader but with a radical difference – he served and gave lead in service in undertaking such activities as proclamation of ranks, organizing concerts, replenishing the library, introducing the school orchestra, correcting the errant, radiating bonhomie at night recreation.

At this period quite a number of brothers in the IndianProvince, and indeed throughout the Congregation, were seriously worried over the practice of nearly unlimited terms of office that was becoming the norm and that the letter of the Constitutions permitted. Evangelist had been given the matter careful consideration for some years. He saw that the practice was beginning to create disaffection in many genuinely sound but worried religious men who shared his misgivings. They saw the threat of stagnation in their lack of a sense of participation in the government of their congregation, the rules of which were becoming more and more regarded as impositions from above (and outside). They felt that the frustrated mood of so many brothers was already beginning to distort the healthy growth of the whole body and the apathy and cynicism creeping in could do untold damage to the Institute. Evangelist’s dilemma was one of conscience; whether to abide by the ruling as it stood, which would simply maintain the status quo, or to represent matters to the Holy See. After much careful consideration and prayer for enlightenment he decided, in the best interests of the congregation and the province he loved, to go ahead and make formal representation. By now he was convinced that passivity in the face of patent unrest in the province could only bring disaster. With J. E. McCann no though of self entered his reckoning. In fact if he were selfishly inclined he might have dismissed the problem as the mere striving for unattainable ideals by a group of sincere but misguided religious, and thus become in a certain sense a beneficiary of the system. He chose otherwise because he cared, and cared deeply; and, be it noted, he first lived the life ((at this time he was forty-five years old) before he essayed to make a specific change in it.

After the 1935 provincial chapter, while in his second year as superior of St. Patrick’s, he put together a letter to the Holy See stressing the fact that certain articles of the Constitutions needed overhauling, which in his view could only be accomplished if Rome looked into the matter. He sent copies of that letter to each of ten senior men in the province, asking them to read it carefully and, if the letter met with their approval, to sign it and send it to the Sacred Congregation for Religious. Any of the ten who did not approve of it were requested to destroy it and forget about the matter. As far as he could gather, the result was negative, for he got no reply; but that a copy (probably his) reached the Holy See was certain, as subsequent events proved.

Those troubled years, agonized over by mature brothers in various provinces, were especially trying for Evangelist. Yet he never faltered in his principles though the price he paid was high, and the fruit only came with the Hannon visitation and the amendment of the offending articles of the Constitutions.

In retrospect the brothers have reason to be grateful to the Evangelist McCanns of that difficult period for the Congregation because they were faithful to their charisms. They were our prophets who affected the progress of the Congregation in the 1940s and largely suffered in themselves the growing pains of the Institute at that period. We can only surmise how the Congregation would have emerged after Vatican II if the question of government had not been satisfactorily settled thirty years ago.

St. Michael’s, Kurji, brought its own quota of happy and anxious years. As usual with JE there was a fine sense of community, and the school waxed strong. World War II came, and with it food rationing, which particularly affected our Indian boarding schools, and catering for the boarders became a nightmare. Then in March 1942 St. Patrick’s and St. Vincent’s boarding schools in Asanol and St. Edmund’s in Shillong were occupied by Allied Army and Air Force personnel; so the major problem of trying to accommodate the displaced boarders had to be faced. Evangelist and the St. Michael’s community did their utmost to help, and within a short time, the number of boarders had risen from 200 to 450, making the business of administration and organization extremely difficult. Evangelist and the community in their Christian love did herculean work for their pupils, and really rose to the emergency. To add to their troubles the “Quit India” movement that same year caused them much worry. The movement, one of the many phases in the struggle that eventually brought about independence in 1947, was political but in the local situation all foreigners were targets; so for five memorable days electricity and all foodstuffs were cut off from St. Michael’s. The climax came when a hostile mob surrounded the school and threatened to burn it down, but at this stage the local people, who had experienced the kindness and gentlemanly behaviour of the brothers, came to the rescue and the danger passed. Evangelist the while was untiring in his efforts to clarify the school’s position with the agitators and his unruffled demeanour calmed the emotions of the whole school.

Once again his term of office as superior suffered an untimely end, but this time for a different reason. In January 1943 the Apostolic Visitor, Reverend John Hannon SJ, appointed Brother John Evangelist McCann provincial superior of the IndianProvince. In this appointment the hand of God was evident for during that critical decade the province was beset with many problems and trials that only the strongest could cope with. He proved equal to the task.

That same year the Government of India through the local National Advisory Committee made big efforts to have the brothers conscripted into various armed services. Evangelist recognized at once the danger posed to the province and indeed to the brothers’ vocations. The possibility of being drafted was very real, and neutralizing it demanded great tact and diplomacy. He, in his cool characteristic manner, managed to do it but only after many interviews with high officials, reams of correspondence, and hours of informal talk with people of influence. The result: The Government of India Defense Department granted exemption to the Christian Brothers form all military service. It was all the more spectacular as many adherents of the British Raj felt that Ireland should have entered the war on the side of the Allies. It shows the extraordinary power Evangelist had of impressing people and winning them over.

That same year, 1943, the building of the new orphanage at 103 Dum Dum Road, Calcutta, came to a standstill owing to sky-rocketing costs and the rigid control of steel and cement, which were being diverted to military requirements. It meant the building would remain unfinished till after the war. Evangelist learnt that the American armed forces, engaged in the Burma theatre of war, were in need of buildings in and around Calcutta. He promptly contacted the American Authorities and offered them the orphanage for the duration of the war but on condition that they completed the building according to the plan. They readily agreed and in a short time the orphanage was completed. It was handed back to the provincial in 1946 and in the following year the old Catholic Male Orphanage at Murghihatta moved out to the new and more commodious St. Mary’s Orphanage at Dum Dum. Had he taken the other course and waited to complete the building after the war, the exorbitant costs would have made it quite impossible for years, and would have strained the resources of the Province.

When Evangelist assumed office as provincial, there were many brothers whose vacation in Ireland was long overdue. They had been assured that they would be given a holiday home after ten years but the promise was not honoured and many of them were chafing under the strain. As it had worked out before the war, only two brothers a year were given the chance to go home for a holiday – and none during a chapter year – which presented a very bleak picture for the younger men especially. The war of course put an end to going home, so that by 1945 the problem was acute in the extreme. Evangelist himself had been, and was still, one of the many sufferers in this respect, for he had not returned to Ireland till 1929, after twenty-one years on the mission, and the next time he visited Ireland was in 1947 as a member of the general chapter after thirty-nine years on the mission. However, he was not the one to complain but he could sympathize with many of the others who did. When eventually in 1946 and the years following, the brothers did get home for their long-overdue holiday – and he arranged large groups to clear the backlog – some elected to stay in the home provinces and quite a few sought and received dispensations from their vows. This was a hard blow to the Indian provincial and to the province as a whole but Evangelist put his trust in God and steered a steady course.

To add to his worries the Province was in dire financial straits as three schools especially, namely the Orphanage (St Mary’s), MountAbu, and St. Aloysius (Quilon) had been a heavy burden. Evangelist recorded in the annals that ‘the year 1948 will remain an unforgettable year in the history of the province; it was spent in meeting one financial difficulty after another. The military declined to pay claims against them and creditors pressed for payment. Ireland, America, and Australia generously gave us financial help.”

The dearth of vocations to the novitiate was another source of worry to the provincial. In 1945 he wrote in the annals: “The novitiate, which had so bravely kept going during the war period, closed down this year owing to lack of suitable subjects.” But in 1951 is the entry: “The novitiate is being reconditioned to meet possible applications after a big drive planned for 1951 has been made. We shall spare no effort to get brothers from the country.” He was destined to live to see a great upsurge in the ensuing years, thanks in no small degree to his planning and foresight.

Shortage of food and trouble in procuring essential food supplies were other problems that had to be faced, but Evangelist, well seasoned to hardship, put his trust in God, travelled by tram and bus and foot all over Calcutta in the blistering heat and managed to secure the necessary food permits. During the great communal riots, particularly in 1946 when the city started to tear itself to pieces, food was very scarce and, as Brother James O’Keeffe put it, ‘the brothers in Calcutta on more than one occasion bravely said “long grace over short commons.’”

At the provincial chapter of 1947 Evangelist was proposed as provincial; thus was vindicated Father Hannon’s nomination, and in the general chapter of that year the act was passed that permitted the foreign brothers of the Indian province to go home for a holiday every eight years – a project very dear to the provincial – and a great boost to the morale of the province, jaded after the war years and the frustration of unfulfilled promises.

At this time Evangelist was exercised with the harsh fact that mere academic education was proving a blind alley to many of our pupils as far as jobs were concerned since there were just too many applicants and Anglo-Indian boys no longer received preferential treatment. This was especially true in the case of the poorer boys who could not afford to go on to university, so that in one sense we were educating them for a way of life that for them no longer existed. He realized that nothing could be more pathetic than this, so in 1951 he decided to introduce a technical section in St. Vincent’s School, Asansol. He believed that it would give boys with a technical bent a chance to compete on equal terms with others in the field of technical education. He saw that the country was in need of well-trained young people to man the many industrial complexes that were beginning to dot the “Ruhr of India,“ whose centre is Asansol. This was his major contribution to the new India. The Government of West Bengal was highly impressed with his project and gave a generous grant that enabled him to put his scheme into operation. And so there came into being the nucleus of the present technical complex that operates so efficiently in St. Vincent’s today.

The same year we find a happy entry in the annals. Evangelist wrote: “Overcrowding in our schools by Indian children continues, but shortage of money and brothers still continues to be a problem. The technical school at St. Vincent’s has been opened, and a big drive is being made to get the novitiate at Mount Carmel started again.” He still had his troubles but there is buoyancy detectable in his entry and that buoyancy was typical of the man. He would work like a Trojan towards an objective, but the work and hardship would not dim the silver lining of his vision.

As provincial he certainly had to face many a problem and surmount many a difficulty in a very trying and often very frustrating period. A lesser man would have wilted or broken under the strain, but not so John Evangelist McCann. He was a veritable tower of strength. The difficult period of his provincialship merely served to underline his rock-like character. In time of trial – and indeed in his whole life – he trusted firmly and serenely in Our Lady’s intercession.

Perhaps his outstanding quality as provincial was his great-heartedness. His enthusiasm was infectious and he had a tactful way of bolstering up flagging morale. He would say to a superior who felt unequal to the task before him, “You’re doing a find job! I couldn’t do it better myself!” or to a brother chafing under an uncongenial assignment, “You’re the only one I could get for this job.” Even if the people concerned did not take him too seriously, they did feel that their work was appreciated; and they were encouraged to make a bigger effort. Occasionally he was suspected of prevarication and of making promises that were soon forgotten or of being too subtle and evasive in his dealing with the brothers. Probably the most accurate assessment would be that he used all the adroitness and diplomacy of the accomplished diplomat. His aim was to promote encouragement and a sense of well-being, bending over backwards to avoid negativism in his dealings with others. The monks saw through his little subterfuges, which occasioned a lot of pleasant comment and engendered no bitterness. Like Bernard Shaw he believed that ‘the confidence trick is the work of man; but the want of the confidence trick is the work of the devil.” His great empathy for all enabled him to put himself in their shoes and to understand their feelings and prejudices. Like St. Paul he tried to be all things to all men, and like St. Paul too he was sometimes misunderstood and misjudged.

Evangelist had an extraordinary influence for good on people. Bishops, priests, religious, and laymen of all walks of life were drawn to him and they held him in high honour and respect. Even the wastrels and ne’er-do-wells and those with a grudge against life, generally fell under his spell. He received them with kindness and courtesy and treated them with dignity and respect. He spoke to them as man to man, advised them, and, when he judged the need, gave them a generous hand-out. After such interviews the brothers used to be much amused at JE’s comments, which they knew were used really to cover up his kindness. “Do you see that fellow there? He has wasted my whole morning. He’s a spineless poor devil and has lost his job, and now his wife and children are half-starved. And then he had the ‘neck’ to tell me he owes everything he has to the brothers. I gave the fellow a bit of my mind.” He would never add, though, that he also gave the unfortunate man a generous bit of his purse as well to help him along the way.

In 1953 when his term of office as provincial came to an end, he was appointed provincial bursar, an office he filled with great efficiency until 1960. The financial statement he presented to the provincial chapter of 1960 was remarkably lucid and comprehensive. The difficult years of provincialship, however, had taken their toll on his constitution and so in 1954 he spent some time in hospital for hernia and prostate-gland operations. That, however, did not long hinder his class work, which he resumed in St. Joseph’s, Calcutta, with a boyish enthusiasm. He prepared his lessons with great care, and the delight he felt at being back with a class of boys and the concomitant chalk and duster was obvious to all. He had not lost his touch after years of administration. In 1954 he was transferred to GoethalsSchool, Kursoeong, where the bracing climate restored his health. Here he was back again in the classroom environment he gloried in. In the evening after school he loved a brisk walk, and he was a familiar figure in his white habit and sola topi, which he always donned the minute he left the house. Quite often on school holidays he would be seen moving off with a group of boys for a long trek in the hills and it would be hard to decide who was the more eager, the boys or the brother. On these outings they studied together all that came their way, be it tea growing or tea processing (the big industry of Kurseong region), plant life or rock formation; and the evenings saw them loaded down with many specimens for more detailed study later. In fact Evangelist was quite an authority on rocks, as the museums set up in St. Vincent’s (Asanol), St. Edmund’s (Shillong) and Geothals itself bear witness. He was fond of telling the story of Brother Stanislaus O’Brien’s visit to the growing museum in St. Edmunds. Stan was not much interested in rocks so when Evangelist pointed to a new specimen and said it was gneiss, Stan said he saw nothing nice about it for, it looked the same as so many other specimens! These outings were in a sense an extension of his happy blend of discipline and freedom in class, where ideas flowed freely from teacher to pupil and indeed from pupil to pupil. His sympathy with the class was readily recognized and boys were proud to have Brother McCann as their teacher, and certainly in his class they were participators, not passive listeners. He was meticulous in preparing the moral science lesson, delivered three days a week to the non-Christians of the senior classes, for he feared that mere academic knowledge without essential values could be dangerous.

His golden jubilee in 1955 was for him an added incentive for deepening and renewing himself as a Christina Brother and of course the whole province acclaimed him on this worthy occasion. For him it was the signal to intensify his reading, which was broad and deep and was indicative of his many interests; geology, astronomy, history, literature, and theology were his standard fare even during hot free afternoons. No siesta for him, and, amazingly, rarely a sign of lassitude, no matter what the mercury indicated. Or he would dash off a number of letters in his own inimitable fashion. He was always a great correspondent and never allowed letters, personal or official, to remain unattended to. With such zest for living it is no wonder that he was so dynamic and resourceful in and out of the classroom. In this sense he never ceased to grow, which accounts for the freshness he brought to the classroom. Nothing static here; he was quite certain the future of the pupils would be different from that of a generation previously and he adapted accordingly.

He continued at the same pace when he was transferred to Shillong in 1959. Shillong was probably his favourite place though he had not lived there since 1929. To supplement his class teaching, now curtailed but only by a period or two, he took on the job of librarian, which he used to maximum effect in directing the boys in their reading. He was a most reliable and painstaking chief invigilating officer for the Shillong centre of the Indian School Certificate Examination for the following decade and more. Never was there a slip-up in this demanding task. He was for the same period the editor of The Edmundian, an assignment that he loved because its scope was wide and it kept him in contact with the activities of the whole school at all levels. For him it was a glorious extension of the apostolate of the classroom. The boys saw him simply as a friend and guide and, on rainy evenings after school, day scholars used to rush to his room for the loan of umbrellas, of which he seemed to have an inexhaustible supply, unclaimed umbrellas usually ending up in his room.

Evangelist was now in his old age, a slightly stooped figure, but the spring was still in his step and the alertness in his eye. His very presence imparted a sense of security – he was dependable, forthright, venerable, a kind of father image. The scholastics revered him and yet felt free enough to indulge in the usual banter with him. Each Sunday morning, after the community Mass, saw him wending his way to the cathedral for the parish Mass, followed by a round of brief visits to lonely old people who literally met Christ in him, in his kindness, buoyancy, faith, and hope. The community, now privileged to see him in the ripeness of his years and in his perfection as a man, loved and honoured him, and consulted him on all sorts of issues. He was at his best at a gaudeamus, with the whole community seated around the fire of a winter’s evening and Evangelist in the centre holding forth on a variety of topics or recounting past experiences. He was a born raconteur and for this reason, time and time again, the brothers jockeyed him into dominating the conversation. Even now in his late seventies and early eighties, the old resilience was forcefully present and the routine that the aged are said to cling to was used by him to streamline his time for creative work. He took an interest in everything and everyone, especially the sick or depressed. In his last years he himself was, on and off, a patient in the Welsh Mission Hospital, Shillong, ad so organized was his day that he found it too short to get through his programme of reading, now mainly post-conciliar in content. He loved the evening visits of the brothers and even after a painful operation was enthusiastic in discussing his current article of study and in hearing the local news. He appreciated little acts of kindness done to him, though in his later years he was a reluctant receiver, which was probably part of his fight against the constrictions of old age.

Out of hospital he at once resumed where he had left off, and the daily round continued. He loved a walk in the cool of the evening in the beautiful hills near St. Edmund’s. He had a keen appreciation of the marvels of God’s creation seen in nature. And he had an eye for such marvels. He bewailed every Peter Bell of the world with the lines:

‘A primrose by the river’s brim

A yellow primrose was to him

And it was nothing more’

And he often quoted them to back his argument. He spent years trying to deepen the sensibilities of generations of pupils and making them aware of G. K. Chesterton’s aphorism that ‘the world can never starve for lack of wonders but only for lack of wonder.’

But with the years, illness kept dogging him and in May 1972, when he had spent nearly two months in hospital with little benefit, it was decided that Evangelist had better go home to Ireland for further medical treatment. After a short stay in the MaterHospital, Dublin, where he had a successful operation for a fistula that had been bothering him, he went to Ballyhaise, Co. Cavan, to holiday with his people there, and to convalesce. He made magnificent progress and wrote back to the brothers in India telling them the good news that he had already made his plans to return to Shillong in August.

Then at 9 p.m. and in broad daylight on 26 July tragedy struck. He had been visiting his sister, Mrs. Danny (Edith) O’Rourke and was crossing the road to his brother’s house nearby when a passing car knocked him down. He was rushed unconscious to the CavanSurgicalHospital, where he died at six o’clock next morning. His brother Leo put it thus: “The surgeon had high hopes at first that he would recover but it was God’s will he should end his life where he began his work sixty-seven years ago – in Ireland. My brother had seen all his relatives and friends around Ballyhaise and was preparing to return to Dublin to start on a quick tour around the South and west of the country before returning to India. He had quite recovered from his operation and was in the best of health and spirits, and looking forward to his being back in India soon again. He was laid to rest at Marino on 29 July and there were few dry eyes during the solemn burial service in the beautiful chapel in Marino.”

The news of Evangelist’s death shocked and stunned the IndianProvince. It was so unexpected, so humanly unacceptable, especially in view of his fine recovery from the operation and the wonderful assurance of his early return. JE could not be dead, not for years yet; there must be some mistake. This reaction was in a way the province’s compliment to its giant: that it found it so hard to be reconciled to the death of a man eighty-two years old. The shock waves gradually subsided with the solemn recitations of the Divine Office and the Masses offered in the different communities for the eternal rest of that gracious figure. Bishops and clergy, in their panegyrics at the Eucharistic celebrations, spoke of the deceased in hushed tones. They had known and esteemed him for years and all saw in him a modern Abraham, “one who walked with God”: they talked of his rich personality; his warm humanity and spontaneity; his kindness, understanding, and giving; his Christian brotherliness. Newspapers gave banner headlines with photos of the deceased and lengthy articles on his contribution to education in India. The Assam Tribune dated Saturday 29 July 1972 carried his photograph on the front page with the simple inscription in large print “Brother McCann Dead.” This was followed by an account of his major achievements in the field of Indian education and his wisdom in helping formulate policies at the various educational conferences over many years.

And then the letters of condolence began pouring in to the Shillong community – from brothers, from priests, from nuns, from past pupils, from friends, from an amazing cross-section of people whose lives Evangelist had touched with something of Christ’s glory over the years. Brother Baptist Finn, a comparative new-comer to India, writes:

“His death is a province-wide cause of grief but it is only proper that the Shillong community in particular should be commiserated with. The circumstances of his death were tragic and yet, somehow, rather fitting. One could not imagine JE being invalided or slipping into senility; he was so active and alert. The memories he leaves behind will be full of dash and verve, whether of his foraging about with a sheaf of papers and photos for the school magazine or hitting a golf ball about the lawn.

“It would seem too that the province has been cheated by his death and burial in Ireland. His rightful place, one would imagine, should have been with Stan O’Brien, Baptist Culhane, Ansie Cooney, and the other brothers who have found a last resting place in the Khasi Hills. But perhaps it is better that his spirit, a spirit of absolute dedication and self-sacrifice, be free to wander over the whole province, and not be restricted in a sense by an Indian grave. Then there is the old Irish wish Slainte chugat is bas in Eirinn! )”Good health to you and –when it’s time – may you die in Ireland!”) That was the ultimate in greetings and one which JE earned to the utmost.”

Kalyan Gupta, a Hindu past pupil writes: “I could not believe my eyes when I saw the heading “Bro. McCann Dead” in the Assam Tribune. I read and re-read the article and was beside myself with grief. Brother McCann was one of my best teachers and I was fortunate to be his pupil for two years in Classes 7 and 8. I had developed a very close relationship with him and many a time he saved me from inevitable punishment from the principal. On rainy days he would gladly lend me his umbrella to go home. Sometimes my sister would come to school to speak to him regarding my studies and he would always assert that I was one of the best boys in the class. All these are small things but they really count.

“I still can’t believe that he is no longer with us. I can almost picture him in my mind at this moment. The more I think of him the more unhappy and sorry I feel for his loss. I can now only pray to the dear Lord that his good, great soul may rest in peace.”

On receiving the sad news the Inter-State Board for Anglo-Indian Education made immediate plans to dedicate their next Quarterly Educational Review to the memory of Brother McCann, and in London, the Old Goethalites Association took steps at one to initate the “Brother McCann Memorial Scholarship”.

With the letters of condolence many spontaneous tributes to Evangelist began to flow from his friends. His niece, Miss Margaret Hayes, writes:

“It was in 1947 that I first met Uncle Jim when he came home on vacation from India. I remember how excited everyone was, and I remember clearly the events of that visit. He was at the time tall, handsome, with an unmistakable distinction of personality. It did not take long to observe his plain, frank kindness; the affectionate earnestness of his speech and manner; the truth which was stamped upon his every word and look. He was a relaxed person, patient, kind, and sympathetic.

“During the long summer we explored the countryside, walked for many hours through the country fields and lanes. At other times we would sit on the bank of the river and listen to the singing of the birds, the fall of the water, the rustle of the rushes, and admire the beauty of the waving grass, the deep green leaves, and the wild flowers, or we would stand on the bridge and see the river playfully gliding away among the trees.

“We all derived much enjoyment from his company. The evenings were spent playing games, or listening to stories about India. By reason of his keen eyes and sure memory, his vast experience and his sense of humour, he had stored in his mind the memories of all sorts of characters he had observed here and there, and we listened spellbound while he recalled these for us. No place was too insignificant nor any happening too ordinary not to attract his attention.

“The months sped all too quickly, and I cannot say what was in my whirling thoughts when the time came for him to return to India. I can only remember the sorrow. After his return and during the years that followed he wrote many letters which were simple and plain-spoken, and written so persuasively that one had to give them attention.

“He made several visits since then, and my admiration for him increased on each meeting. The richness of any personality can only be realized in personal contact. He was a man of many resources, and so easy to get on with. Looking back over the years, one thing that made the most impression on me was his love of children, and his ability to communicate even with the smallest toddler. He could not help loving children; their innocence, their truthfulness, and their simplicity appealed irresistibly to one who was himself essentially childlike in nature. That which radiated from him was both love of God and a desire to see God’s world grow better.”

At the end of a long article in The Herald dated Friday 11 August 1972, and headed “J. E. McCann: a Name Revered Among Brothers’ Boys,” the editor, Horace Rezario SJ, has this to add:

“In gratitude to the memory of this great teacher and leader, I feel constrained to subscribe two personal recollections of Br. McCann. One is of a hall packed with boys of every age, engrossed in listening to the principal. The occasion was Sunday when, as every Brothers’ old boy will know, the congregation used to prescribe a period of religious instruction. From the classrooms, Br. McCann would assemble all in the largest hall and spellbindingly speak of saints and devils, of scouting, good manners, games, some personal experience………And though that was, by rights, a holiday and the bell which signaled the period’s end beckoned to lunch, its sound was received with universal dismay.

“Years later, as a newly ordained priest, I met the former principal, at Goethals, and realized anew his brilliance as a conversationalist. Brother McCann made one want to speak. Like a host whose discreet attention notices every need, his art was in bringing conversation always within easy reach of the guest. Meanwhile there was that never failing poise of the perfect communicator.”

From the community of St. Mary’s Orphanage, Dum Dum, came the following appreciation:

“The mention of Brother J. E. McCann invariable brings to one’s mind a picture of a stately gentleman, slightly bent, making his way around the school or the compound with his ubiquitous topi guarding his thick crop of white hair or clutched under his arm. Sparkling blue eyes carefully took note of everything and always shared with his lips that smile which accompanied most of what he said.

“Tongue-in-cheek remarks were a specialty with Brother Evangelist. Most of the brothers can recall famous sayings of his, such as that made on the occasion when the house named in his honour in St. Edmund’s was celebrating its victory in the annual sports. The party was almost over when Brother Evangelist was called on to say a few words to his team of athletes. The speech was short and to the point. In an effort to fire the assembled throng, Evangelist with due dignity and a fitting cough continued, “As the motto of our House says, ——–” There was a slight pause, during which the speaker leaned over to ask the house captain, “What is the motto of our House?” On being told he went on with his talk without a blush.

“Even with the passing of the years, Brother McCann never grew old. A teacher to the end, he was also the life of any party when the brothers assembled for an evening’s fun. Stories of olden days and tough times flowed freely then and Brother’s eyes would flash with merriment as he recalled them. His memory for dates and names was remarkable and his gift for summing up people was as unique as the language in which he did it.

“The history of the Christian Brothers in India was his forte and it was a treat to be with him on the annual picnic, when he was wont to let himself go in the good old ‘when- I-was-young’ fashion. It was then that one felt glad to belong to the proud pageant of Christian Brothers. The pity of it now is that he never got round to writing the history of the province. So much is lost with him.

”Like so many other great men in general and great Christian Brothers in particular, Brother McCann was a real apostle of charity. His love for the Congregation abounded and flowed over into the lives of those poor neighbours who figured more and more in his circle of acquaintances. He made life that much easier for many, and untold numbers of homes in Calcutta used to look forward to his visit. God alone knows what his servant did for him but, as the poet points out, it is better that way.

“Paid by the people, what dost thou owe

Me?” – God might question; now instead

“Tis God shall repay; I am safer so.”

De Britto Curran gives us his impression of Evangelist McCann as a religious:

“When the impact of the Second Vatican Council began to make itself felt in our congregation, Evangelist was in his seventy-seventh year; and for most men of that age the changes in the Mass, in the prayer life of the brothers, and in the fresh ideas regarding the religious life in general, were bewildering. It was typical of his deep faith that so far from closing his mind to what was happening, or deciding to spend the few years that remained as he had spent the many that had gone before, he embraced the whole new thinking with an enthusiasm and a great optimism that were infectious.

“A profound faith and a cheerful optimism that never seemed to know the blight of even temporary despondency – these were the characteristics of this great man. Perhaps there were some who, knowing him only in his later years, would be inclined to regard his boundless enthusiasm and optimism as somewhat facile, the optimism of a man who lives on the surface of things. No judgment could be further from the truth. The enthusiasm and optimism of Evangelist McCann were those of a man who had plumbed the depths, who had passed through the valley of the shadows of death, and whose heart had known no fear, because he had walked under the guidance of the Shepherd’s crook. For it had fallen to his lot to guide the destinies of the IndianProvince during the most turbulent and darkest days.

“He had seen his brothers become the mistaken objects of insult and scorn during the “Quit India” period, and had striven to maintain the work of the schools during the terrible years of the war, when premises were requisitioned by the army; had watched in sadness when so many, tired from the thorn-strewn way had left the ranks; had cheered and consoled and encouraged and reassured his brothers during the uncertain days of the middle and late forties. Facile optimism! God send us many more facile optimists!

“It would be profoundly true to say that Evangelist was entirely faithful to all his religious duties, but such a statement would not convey an adequate picture of what those who were privileged to live with him observed in the man. Somehow one sensed a certain élan, a vibrant enthusiasm that showed itself in his whole manner, in the tone of his voice, in his every movement. There was a dynamism, an inward fire that seemed to drive him forward; it can best be explained in the words of the ardent St. Paul “Caritas Christi Urget nos.”

“Many will have noted his devotion to the Mass, the almost boyish ambition to act as sacristan or acolyte that endured to the end, the attendance at a second Mass on Sundays, the study, aye and note-taking, on the new liturgy, the psalms, anything that would deepen his understanding and nourish his piety.

“And with all this there was nothing narrow or strained or small in him. He had about him the openness and the charm and the sympathy and the desire to help of a true follower of Christ. The youngsters loved him, the non-Christians amongst them regarded him as a holy man, a saint, and said so; their parents, on contact with him – and this despite the fact that he had passed the three score and ten – wished to have their boys in his class, particularly if those boys happened to find themselves in a class taught by a lay master.

“It is unfortunate that in the spate of writing provoked by the documents of the Second Vatican Council some of the wonderful insights contained in those documents have been so constantly repeated that certain words are in danger of passing into jargon. One such word is “Commitment.” We are told that the essence of the religious life lies in the total commitment to Christ which a man makes of himself at religious profession and the fidelity with which that commitment is lived. Brother Evangelist McCann, in the considered opinion of many brothers who lived with him, was a man who to the last day of his life, lived out the commitment of his profession in an outstanding manner. His fidelity to prayer has already been mentioned; his dedication to the apostolate of the classroom was patent. Though he was in his eighties there were few indications that he was an old man. His mind was remarkably active and enquiring; there was still a spring in his step and even in the last few years of his life he might be seen heading up the hillside with a group of boys of twelve, thirteen, or fourteen years, and the pace set was not what one would expect from a man in his eighties. Consequently, when a considerate superior wished to lighten Brother’s work in the classroom, Evangelist was the first to protest. He was still capable of doing the work and earnestly requested that he be allowed to continue.

“I shall not readily forget one of my last meetings with Brother Evangelist shortly before his death. He was in St. Patrick’s, Baldoyle, awaiting the call to MaterHospital for an operation. In the course of conversation he turned to me and said, “You know, I don’t fit in here. There men here are incapacitated in one way or another. If this is cancer I’ve got (and he mentioned it as casually as if it were a common cold) then it is a different matter; but if it something that can be set right in the hospital, then I want to get back to my work in India.” The man had given more than sixty years of his life to India; he was prepared to keep on giving. His commitment was total and this desire to live it out was as vibrant and enthusiastic at the end as if he were just beginning. That was one of the extraordinary things about him; where one expected the twilight of the evening, there was the dewy freshness of the morning.

“Che uomo completo!” was the phrase used by Pope Pius XI when speaking at the canonization of St. Thomas More, and surely that phrase can be applied to the Brother Evangelist we knew. Perhaps it was but in the last decade of his life that he had heard the word “fulfillment’ used in the context of present-day spiritual writing, but in his life he had achieved it triumphantly. Here was, without any shadow of doubt, ‘the complete man.’”

Monsignor E. Kouwen, St. Thomas’s Presbytery, Calcutta, ponders on the death of his friend:

“Knocked down by a passing car, Brother Evangelist McCann died on 27 July 1972. We had been informed of his remarkable recovery after a serious operation and had been hoping to have him back when news of his death shocked and saddened us.

“I first met him when he was teaching the Senior Cambridge in Calcutta. His pet subject was chemistry, whereas his then hobby (for which we must blame Brother Leo Maher!) was geology. We were, of course, too small for his chemistry class, but scouting and KBS gave him opportunities of meeting smaller boys. He understood boys, had a real appreciation of their aspirations and their problems. He loved to be with them and their happiness delighted him. He would put himself out, at any length necessary, to keep them interested and happy. Accompanying him to the villa at Dum Dum, whether for a day out or just for a swim, was always great fun.

“He had the great faculty of alway being able to smile and be kind. For hundreds of Christian Brothers’ boys he is “My Most Unforgettable Character.” When old boys get together, McCann is always spoken of with affection and esteem.

“I think his best years were spent in Shillong. He first went there as principal of Saint Edmund’s where his cultivated sense of what was right and fitting left its mark on the college. Modest but forthright in his opinions, conscientious in his duties, humble in his approach to God and men, he was able to work well with both brothers and boys. He commanded respect without seeking it. He taught by precept and also by example.

“Now for just one personal glimpse. It was customary for the Senior Cambridge Class to have extra periods when the examination was near. After supper we were in the chemistry laboratory, fooling around while waiting for brother McCann to come. Gibbon said something chirpy to Gorman, who in a flash had him by the neck, in the crook of his arm.

“’Say Pax!”

“’Never.”

Well, when Gorman got tired holding him he let go. How horrified all of us were to see Gibbon drop like a log! We shouted at him, shook him, splashed water on him, but there was no sign of life.

“’Hell, I’ve killed him,” said a shattered Gorman.

Brother McCann came in:

“’What’s going on here?’ he asked.

“To our hurried and confused explanations he hardly listened. He promptly got down and began artificial respiration. After a while, to our great relief, Gibbon showed signs of life and soon got up after fingering his throat. Brother McCann saw how shaken we were.

“’Off to bed the lot of you; you’re not fit for class tonight.’

“No anger displayed, no scolding, no threat of punishment.

“’Hell, but he’s super,’ whispered somebody.

“Only a man very intimate with his Maker can always be master of the situation, can act calmly and promptly in such a situation.

“How hard it is to command those vowed to obedience! One always has the greatest sympathy for religious superiors; theirs is a responsible and difficult task. Brother McCann had a long term of office and was admirably suited for the role. As provincial he was the unassuming, efficient administrator with whom it was easy to cooperate. Always approachable, if there was a kind way of saying what had to be said, or doing what had to be done, he knew it. If a rebuke had to be given or a correction made, it was done with such delicacy that it was accepted as well understood advice. The Master, whom he studied in his morning meditation and private reading, had left his imprint on him.

“The good Lord permitted Brother McCann to go well beyond the ‘three score years and ten.’ But for him the added years were not ‘years of labour and sorrow.’ He continued to work despite bouts of illness, and if reference to his pain was made, his comments would be preceded by an apology for even mentioning the subject. He could never remain idle and his interest in everything going on was not less keen than in the years of his zealous vigour and strength. He continued to enjoy the esteem and affection of his brothers, was happy with them everywhere, but surely happiest in St. Edmund’s, the house he loved so much.

“Meeting a Jesuit who had just returned from preaching a retreat to the Christian Brothers, I enquired after Brother McCann.

“’You met Brother McCann there? How is he?’

“He’s a prince!”

“Yes, graciousness was an outstanding characteristic.

“’No one in this world is perfect; so we must suppose that Brother McCann had his imperfections. But he possessed qualities and virtues that crowded them from view. He judged softly and had a deeply human understanding. He has always been a good friend to priests and a wonderful host. But the kindness he extended to priests in trouble must ever be remembered with gratitude. His tact, sympathy, and concern could only beget a peace that calmed troubled hearts, and they were enabled to resume work again.

“’As a close friend of Brother John Evangelist McCann for over fifty years, I thank God for his friendship. May the joy with which he lived this life be fulfilled in the total joy of life everlasting.”

Father Terence Lewis SJ preached at a special requiem Mass in Calcutta:

“’The news of Brother J. E. McCann’s death must have brought a deep sense of loss to many. That is because the list of those indebted to him was large. Yet, I feel sure that this sense of loss was different for each person. Brother McCann’s was a rich, ample personality. His quick mind and sure intuitive sense not only gauged the wave-lengths of individuals; they also helped him to adapt himself to their vagaries. Hence at this time, he is remembered with thanks by a number of people who, while mourning his tragic passing, hold his memory in benediction.

“’I came to know him when I was fourteen. This is the age when every boy is imperceptibly a hero-worshipper. What attracted us to him was his manly way of dealing with boys. He was very decisive in what he did, and precise in what he said. Moreover, there was a certain evenness in his dealings with us. He never had any favourites. Coupled to these qualities of mind and heart was a versatility of action. This came out especially when we worked with him to produce plays. He was scene-painter, stage manager, costumer, director, often playwright as well. All these he did with what we thought was a good amount of success. That made me once remark to him after a play, ‘You know, sir, the only thing I could ever beat you at is handwriting!’ He laughed, but he was too good an educator to let the opportunity slip. ‘The things that matter in life,’ he said, ‘are not so much the individual as the corporate successes that one achieves. As experiences, they are far richer and more rewarding.’

“’Every now and then we would gather in assembly to hear him talk. One criterion of a good speaker is his ability to stir his audience. At one such talk, we had been impressed and told him so in so many words. His topic had been the conversion of Mary Magdalene. A bit chary of our appreciation, he asked each of us to say what, in particular, had impressed him. I remember saying it was the title by which he had described Mary Magdalene. He had called her ‘The Night Queen of Magdala.’ Brother smiled when I said that and retorted, “The expression is merely a euphemism for a rather notorious woman. But even such a one, when touched by the grace of Christ, can become a great saint. And so my title was not “The Night Queen of Magdala, “ but “The Night Queen of Magdala on Her Knees.”’

“’Brother McCann was all his life a strong walker. Much of his good health, he claimed, came from walking. But he liked to lace a walk with talk. Hence we who went out with him soon learned the formula: a good walk and a bright talk. Often we would put our questions away for these occasions. I remember once writing in my diary, “Must ask McCann about the sphinx.’ When I did put the question, he inquired what had stirred my interest in that monster. I said it was the mere sound of the word. At this, one of my friends began to twit me. ‘This chap, sir, is still in the nursery rhyme stage. He is enamoured of words just for their sounds.’ That comment was the spring-board for Brother to plunge into an interesting explanation of the relationship between sound and meaning in the evolution of language. He concluded by saying that perhaps I was an incipient poet who one day might make a creative use of language. That was just like him, always pointing to the significance of things which at that age we were unable to understand or explain. I must add I never became a poet; instead I joined the Society of Jesus!

“I cannot forget how, when that prospect first percolated into my consciousness, I was scared. Fortunately I had someone by like Brother McCann, in whom I confided. ‘Fear,’ he maintained, ‘was something one had to learn how to overcome in the process of growing up.’ To do this, one had sometimes to resort to natural means; at others, to supernatural; and on still other occasions, both had to be employed. In my case, I had to pray for strength and light. Over and above, I had to learn who the Jesuits were. They were first and foremost religious. To understand better what this meant, he got me to read a book called Western Monasticism (I forget who was its author). The Jesuits were also apostolic men. And so to supplement the first book, he asked me to read another on the priesthood which had been developed from the point of view of the Cure d’Ars. I was not the only one for whom he put himself out in this way. Another of my friends was keen on becoming a forest officer. Brother McCann also gave him all the help he could in the way of reading material. He also arranged an interview for him with an official of the Forest Department. That is how he made himself all things to all his boys.

“’A man who was such a strong influence for spiritual good must have been closely united to God. About his interior life, Brother McCann was very discreet. Yet one remark of his is still remembered. Every year he looked forward to his annual retreat. For him it was always an occasion of grace and discernment. When there was public adoration, we found fifteen minutes interminably long, while we noticed Brother would spend more than an hour before his Eucharistic Lord. In his congregation he had occupied many responsible positions, but the job he loved the best was to be sacristan. In his talks, too, he would emphasize the point that, if we wished to grow spiritually, we had to approach the Eucharistic table. When he found a boy all mixed up and scrupulous about going to Holy Communion, he had a special way to help him. It was a way which only a zealous, resourceful brother would devise.”

And so for Evangelist, the wheel —-from Belfast to Ballyhaise —- has come full circle but though the great heart is stilled in death, the indomitable spirit is alive and active in all who knew him. Somehow the graciousness of the complete man forever renewing himself still lingers. We honour him in death and salute his memory. We honour, too, his fellow jubilarians throughout the Congregation, all those great men who were prodigal in the giving of themselves and lavish of their time and energy and youth and ripeness of manhood in the cause of Christian education and religious life. Requiescat in Pace.

(In addition to those already named, grateful acknowledgment is made to the following contributors: Brothers T. A. Brown, A. E. Conway, D. M. Cooney, C. P. Gaffney, P. C. Hart, F. J. Kelly, E. X. Leonard, M. B. Maher, B. McCarthy, B. C. Morrow, P. S. Murphy, P. M. O’Brien, M. D. O’Donohue, F. O’Reilly, J. A. O’Toole, J. C. Roe, M. F. Walsh, K. C. Ward, Mother Canice IBVM, Mother Madelaine IBVM, et al.)